SMT-able Language and Small-Model Validation

Part of the work on Bosque over our 21kloc experiment involved the translation of Bosque code into SMTLib for logical analysis – both formal validation and testing applications. So, key question is – how well did this work out??

The short answer is – interestingly. The translation to SMTLib is pretty straightforward for many constructs and names are not mangled so it is easy to integrate the solver into a variety of workflows and tasks.

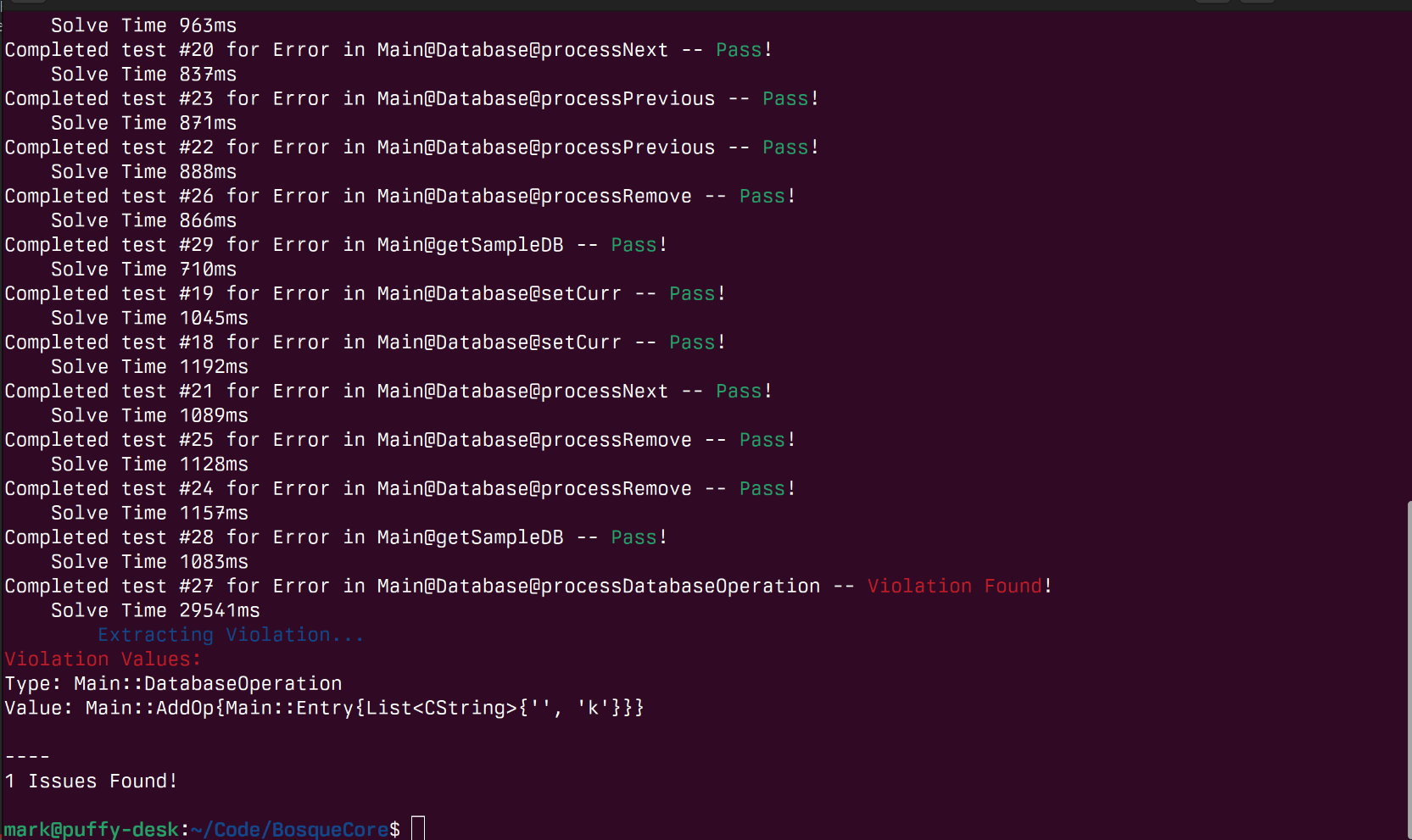

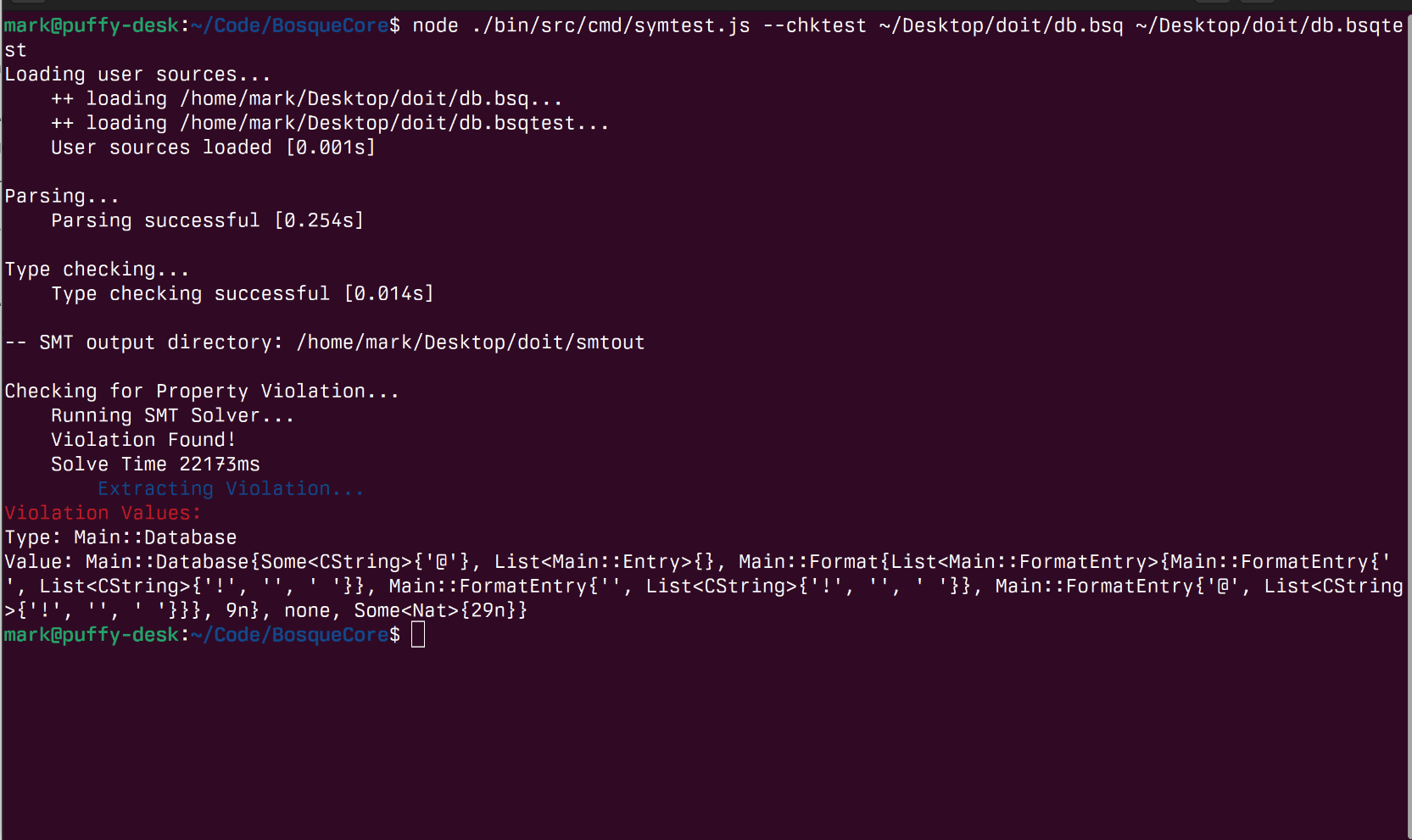

- The highlight is that we can run the Z3 on the resulting SMTLib code and prove correctness and/or find failing inputs for interesting programs (see below for it in action on an in memory database based on the SpecJVM DB benchmark) 👍

- The low-light is that the solver is slower than we would like, particularly on SAT instances, and even slower than an earlier prototype using a different translation approach (3-valued IR vs. tree-based here) 👎

- The cool part is that, this is still enough to be useful for AI agentic tasks 🚀

As an example of the capabilities, we can look at a simple in-memory database that supports basic table creation, insertion, and querying based on the SpecJVM DB benchmark. We can write tests for various components and operations, for example, checking that deleting the value at the current cursor position in a table does not result in an error:

errtest singleOpFailure(): CString {

let db = getSampleDB();

let op = RemoveOp{};

let res, _ = db.processDatabaseOperation(op);

return res;

}

However this only checks that single operation on that particular sample database does not fail. Which is useful but far from sufficient to have confidence in the correctness of the implementation. Instead we can write this as a parameterized unit-test to check, over all possible operations for all possible values, that we will never get an error:

errtest singleOpFailure(op: DatabaseOperation): CString {

let db = getSampleDB();

let res, _ = db.processDatabaseOperation(op);

return res;

}

Awesome! That gives us a lot of confidence in the correctness of our implementation and found one case of a bug – specifically when we try and add a row but forgot to check that the size of the row to insert matches the size expected for the table :( Of course we can generalize this more by allowing the database to be a parameter as well or by checking that a specific property always holds, for example, that after a remove operation the number of rows in a table has always decreased.

chktest removeInvariant(db: Database): Bool {

let rdb = db.processRemove(RemoveOp{});

return db.entries.size() > rdb.entries.size();

}

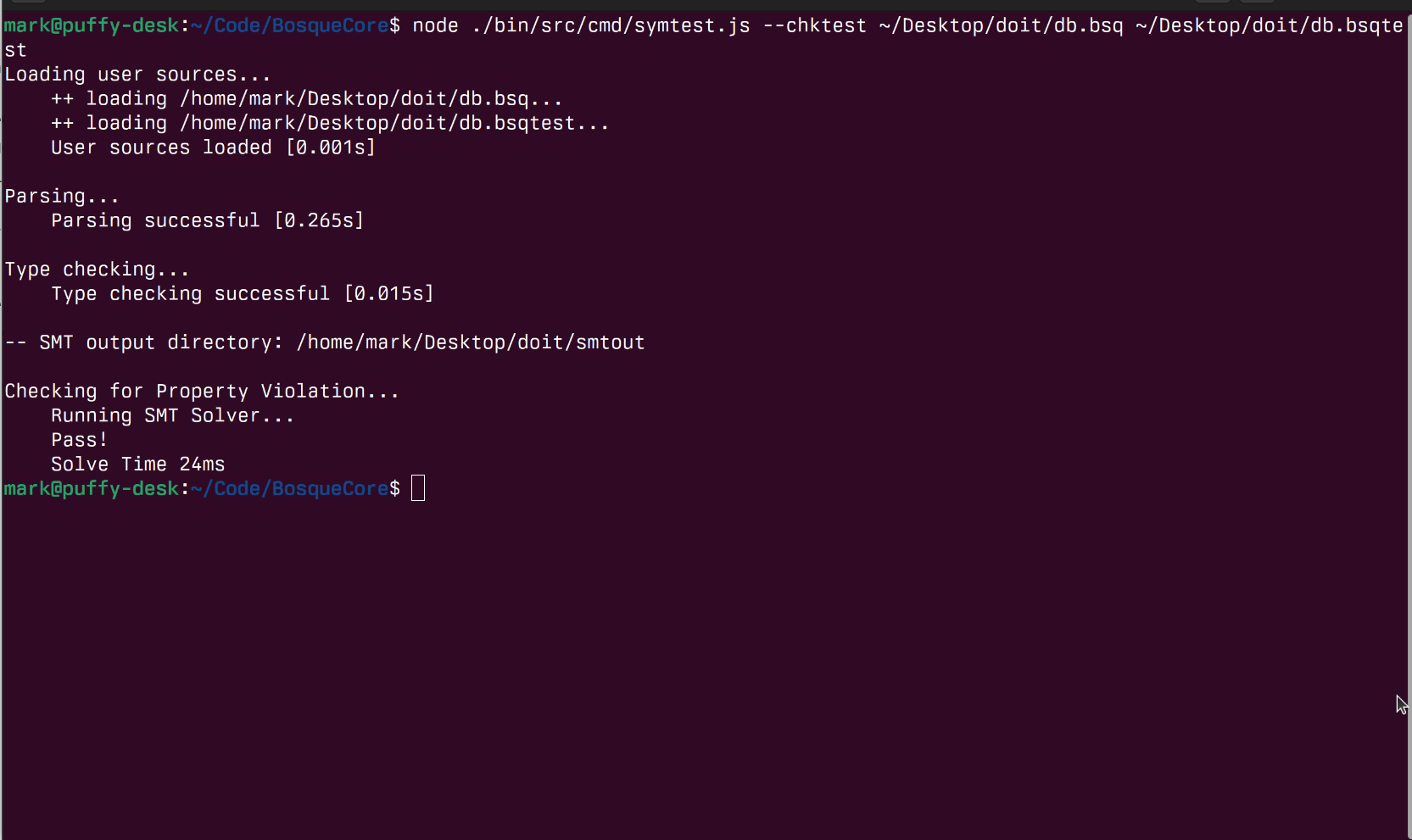

Running this test, obviously in hindsight, finds the case where this property does not hold – specifically when we try and remove a row from an empty table! Updating our expectations to db.entries.size() >= rdb.entries.size(); will then report that this property holds for all small databases and remove operations.

So, how does all this work, what is the relation to agentic AI, and what are the next steps?

Problem Statement

Let’s start off by formally stating the problem we are trying to solve and the approach we are taking. Specifically, we want to be able to formally validate properties of programs written in Bosque. As a general problem, this has been approached in a variety of ways – Abstract Interpretation (AbsInt), Proof-Oriented Programming in languages like Dafny, Lean, F* (Proofs), Bounded Model Checking with tools like cbmc or kani (BMC), and Dynamic Symbolic Execution like KLEE (DySym).

A recent blog from Galois Inc. does a great job of covering the practical challenges to the adoption of formal validation methodologies. Merging these with my experiences, and a bit of rumination, provides a set of foundational principles for creating a light-weight validation system:

- Impact: It is assumed that, at scale, a project will always have a backlog of issues. The priority for validation is to find errors that have a high-likelihood of being hit in some form.

- Severity: Low impact bugs, that do not have security implications or are fast-abort logic bugs, are less interesting than violations of safety properties or business logic rules.

- Usability: The system must have a low barrier to entry for developers, with no need for specialized knowledge of formal logics, proof systems, or validation techniques. Developers know how to write code, tests, and assertions.

- Understandability: Validation results must be actionable and ideally can be opened as issues, with reproduction inputs, in an issue tracker.

- Guarantees: The validation should have a known termination condition, after which, there is some articulable guarantee about what the validation ensures.

Looking at the landscape of techniques, we can see that each has its strengths and weaknesses:

| Technique | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| AbsInt | ✅ Fully automatic and scalable to large codebases | 🚫 Lots of false positives and only checks a subset of (fixed) properties. |

| Proofs | ✅ Full correctness guarantees and works for arbitrary properties | 🚫 Requires (extensive) manual proof work and often specialized knowledge to formulate/complete verification |

| BMC | ✅ Fully automated, can find counterexamples, and works for arbitrary properties | 🚫 No guarantees on the absence of errors -- they may be present but missed by exploration strategy and path explosion |

| DySym | ✅ Fully automated, can find counterexamples and works for arbitrary properties | 🚫 No guarantees on the absence of errors -- they may be present but missed by exploration strategy and path explosion |

Small-Model Validation

Based this analysis and cost/benefit drivers for the adoption of formal validation techniques in industry we can try a new approach for Bosque – small-model validation (SMV):

- The source program is converted into a first-order SAT Modulo Theory (SMT) formula – using only (semi)decidable theories in the construction.

- To ensure decidability of the formula, and leveraging the small-model hypothesis, the sizes of input collections and recursive data-structures are bounded.

- Each possible error is checked individually and independently by proving reachability (or unreachability) from a specified entrypoint using Z3.

- The result is either a proof that the error cannot be triggered with a small input or a model of a witness input value that will trigger the failure.

By construction this approach address the Impact and Understandability criteria identified in the problem statement – any reported errors are high impact as they triggerable with small-inputs and they are easily understandable as we can transform the results into reproducing inputs for debugging. Issue Severity can be automatically ranked by the type of assert failure, eg. a generic runtime error, vs. data-corruption vs. business logic violation.

The methodology is based on SMT solving over decidable (bounded) theories so it is (trivially) fully automated. There is no need for developers to learn an additional proof language, all checks are encoded as functions/methods in the Bosque programming language, and no manual intervention is required to write lemmas or diagnose proof failures. This methodology can be integrated into many workflows – ranging from novel experiences like full validation of a program, to more traditional setups like automated property-based-testing or parameterized style testing.

Conventionally, proof-oriented programming, and the focus on producing a proof of total correctness wrt. a specification is considered the gold standard for software validation. However, in practice there is often a large “information gap” between what a formal specification is capturing and what the developer (customer) believes is being guaranteed. In contrast, the “what” is being checked of the small-model validation approach is clear and explicit as it is just Bosque code and as each error is checked independently, we can guarantee that at termination every possible error has been checked. Thus, we have a strong Guarantee of when validation is complete, what has been checked, and what the results mean.

Making it Happen

The process of converting Bosque code into SMTLib is actually just straightforward compiler style transformations. Code is in the Bosque repository and is pretty much what you would expect – at some point, probably after the next rework when performance is closer to where I want it to be, I’ll have a technical report on this – but just to illustrate the approach we can look at a few examples.

We can start with a simple function to compute the sign of an Int. This code is very similar to the implementation one would expect in Java or TypeScript – in fact just eliminating the explicit i specifier on the literals would make it valid TypeScript.

function sign(x: Int): Int {

var y = 1i;

if (x < 0i) {

y = -1i;

}

return y;

}

The resulting SMTLib output is almost a 1-1 map from the source code and types. We map the Bosque Int type to the SMTLib Int kind, and the if statement to an ite expression. The only real difference is that we need to introduce a let re-binding for the local variable y as SMTLib does not have mutable variables and then convert the control flow from statement blocks to continuation expressions.

(define-fun sign ((x Int)) Int

(let ((y 1))

(ite (< x 0)

(let ((y -1)) y)

y

)

)

)

In this case the only theories/kinds used a the decidable theory of integer arithmetic and equality so this is a fully decidable formula. The majority of the transformations from Bosque to SMTLib are similarly straightforward (and involve only the decidable fragments of datatypes and functions).

The main challenge is dealing with unbounded constructs – specifically collections and iterative processing on them. For example, consider a code snipped that checks if all elements of a list satisfy a predicate or that maps a function over a list:

let x = l.allOf(pred(x) => x >= 0i);

let y = l.map<Int>(fn(x) => x + 1i);

In these cases we map the list to an SMTLib sequence kind and use the lambda support in Z3 to handle the application of the higher-order functions. The challenge is that the theory of sequences is a semi-decidable theory. This means that, if there is an error, that Z3 will eventually find it but if there is no error, it may run forever.

(let ((x (seq.fold_left (lambda ((acc Bool) (vv Int)) (and acc (p vv))) true l)))

(let ((y (seq.map (lambda ((vv Int)) (f vv)) l)))

...

)

)

Now the interesting part is we could assert a set of concrete value for the list l and then the formulas become decidable – let l = List<Int>{1i, 2i, 3i}; This solves the decidability problem but is not very useful as it only checks a single input. However, we could improve on this a bit and constrain the list to have 3 elements but allow any values.

(declare-const a Int) (declare-const b Int) (declare-const c Int)

(declare-const l (Seq Int)) (assert (= l (seq.++ (seq.unit a) (seq.unit b) (seq.unit c))))

This is better as now we are checking the code for all possible lists of length 3. And of course we would generalize this to check lengths in the range [0, 3].

(declare-const l (Seq Int))

(assert

(or

(= l (seq.++ (seq.unit a) (seq.unit b) (seq.unit c)))

(= l (seq.++ (seq.unit a) (seq.unit b)))

(= l (seq.unit a))

(= l (as seq.empty (Seq Int)))

)

)

Or more concisely:

(declare-const l (Seq Int)) (assert (<= (seq.len l) 3))

This key observation, of bounding makes the formulas decidable, and the small-model hypothesis that most bugs can be found with small inputs, is the foundation of the small-model validation approach. With this construction the small-model verifier is now automatically (decidably) check that any error is either infeasible (with small input lists) or will be triggered and generate a small failing input example – as in our initial DB example!

Agentic AI and Scaling Up!

The rise of AI driven coding and Agentic operations creates both a unique need and opportunity for introducing a new software stack. These systems access information and systems, which if misused, can have serious consequences. Guarantees about behavior provided are limited to a statistical statement that, under normal operating conditions, the system will, with high likelihood, behave as expected. This is insufficient for many applications and, in the presence of malicious actors who seek to confuse or mislead an agent, this risk is unacceptable (as witnessed by recent MCP escapes).

This environment poses an opportunity build a new Agentic platform with automated reasoning and safety at the core. The small-model validation process can be used to validate the behavior of the agent and its code, ensuring that it operates within the desired parameters and adheres to any relevant policies or regulations. Alternatively, the validator can be provided as an offline judge during training or as an online tool for an agent to use during test-time evaluation.

Using these techniques we can both increase the overall success rate of the agentic system, ensure that it always operates within specified safety parameters, and provide this transparently as a fully automated component of the overall system!